Part I of this series presented the Prepare-Present-Practice teaching sequence used by Kodály-inspired music teachers. The process prepares students’ readiness for new concepts and skills, quickly presents the new material, and practices it in multiple ways. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate how this approach can be used when teaching concert repertoire in more advanced bands. For the purpose of this article, we will look at Frank Ticheli’s “Shenandoah” as an example.

The prepare stage

Before we can plan preparatory activities, score analysis will help us determine which concepts and skills are new and which can be practiced. While beginning band instruction focuses more on tonal and rhythm literacy and technical skills, more advanced classes focus on complex concepts such as blend and balance, articulation, intonation, phrasing, form, tension and release, style, harmony, and the connection of music to other areas of life. Once we determine the teachable elements within the piece, we can use warmup materials and unison exercises to ensure student readiness to be introduced to the music. For Shenandoah, we may want to ensure they are comfortable with the rhythm patterns involved, the harmonic progressions, and that they have an understanding of the style of the piece.

Shenandoah offers a wealth of concepts and skills to explore. Rhythmically, the piece is filled with ties over to eighth notes followed by eighth note anacruses into the next measure. Tonally, common patterns such as sol-do or do-re-mi-fa-so can be refined while preparing more difficult patterns like fa-la-so or la-mi-so-mi. Students will also be introduced to Gb major, as the score moves to Gb multiple times. Harmonically, this is a good instance to practice non-harmonic tones such as suspensions and borrowed chords from the relative minor.

Shenandoah is a quiet ballad requiring a steady, controlled tone, legato articulations, and an ability to perform borrowed chords and suspensions with expression and in tune. By using directed listening lessons as students enter class, students can recognize stylistic characteristics of similar pieces, allowing them to build the schema necessary to play the music appropriately. To keep them engaged, they can conduct to show dynamic contrast, articulation style, and dissonant spots and their resolutions. Great pieces to use for this include Whitacre’s Lux Arumque, de Haan’s Ammerlandde, Bloom by Steven Bryant, and With Quiet Courage by Larry Daehn. It is also helpful to listen to various vocal versions by folk singers such as Pete Seager or any of the numerous choir performances you can find on YouTube that provide a variety of approaches to the piece.

To develop the literacy and technique necessary to play the piece, technique books can be of great help for preparing scales, basic harmonic progressions, and basic rhythm patterns. Flashcards and “play after me” exercises can prepare specific rhythm patterns and articulation styles. Using Curwen hand signs is also a quick way to teach tonal patterns and, when using two hands, it allows for tuning of intervals.

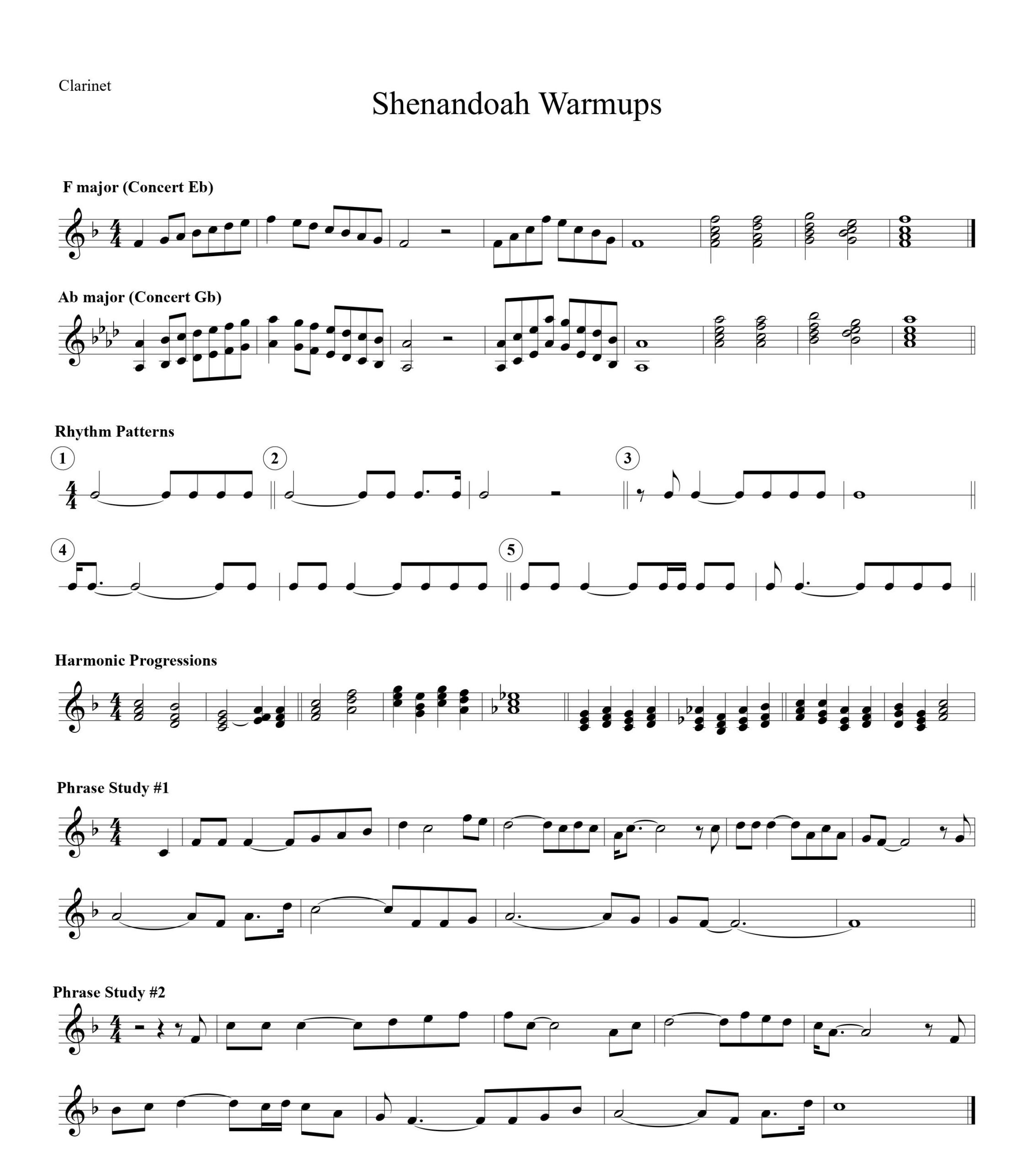

It is also helpful to create warmup sheets (figure 1) that address scale technique, rhythmic reading, tuning, and phrasing. For some pieces, I have created unison exercises based on tricky excerpts that some sections must learn. This keeps people busy while rehearsal time is taken to learn the part, preventing off task behavior while at the same time giving students an extra challenge. For other pieces with intricate interplay between parts, I have written two- or three-part excerpts, transposed for each instrument. This allows students to see how the parts fit together as they play each individual part in unison and then split into each other’s parts.

Figure 1

The present stage

It is interesting to note that language arts teachers expect their students to be able to read at sight 90-95% of the words in the readings they introduce. When we present a new piece to our bands we must ask if our students can do the same. While our choice of music is key to this goal, the degree to which we prepare the students for the unique challenges of a score during warmups also plays a big part in setting students up for success when sight reading.

The practice stage

This stage is where the bulk of rehearsal time is spent. It is when we provide experiences for students to review and refine known concepts and skills and when we put new concepts and skills into context. Kodaly-based teachers know that by deliberately directing student recognition of concepts within the piece, they will be more likely to transfer that knowledge to new situations. They use warmup times to isolate rhythm or tonal patterns through scale work, flashcards, aural dictation, and singing. Then they immediately move to the sections of the music containing these items.

Some concepts and skills, such as tone, technique, and ensemble skills are constantly practiced, and the more students transfer them to new pieces, the more fluent they become. For Shenandoah, the band has the opportunity to practice blend and balance at soft dynamics and maintaining group pulse at a slow tempo through the use of self-assessment and inner hearing strategies. In regard to technique, flutes, and first clarinets will practice their tone in extended ranges, again improved through warmups.

Practice is not just about refining literacy and technique. It is also about understanding music by refining grasp of form and expression, as well as connecting music life. Kodaly-based teachers direct student attention to major sections in music and identify form of each section as well as the whole piece whole. They connect the feelings expressed in the music with the structural events that elicit them. This guides students to use expressive elements appropriately.

conclusion

The ideas described in this article are not unique to Kodaly-based teaching. In fact, the Prepare-Present-Practice process can be traced back to Jerome Bruner’s work in the mid-20th century. However, the methodology guides us through a sequential, thorough process of bringing music to our students. It’s just good comprehensive teaching!

Steve Oare is a professor of music education at Wichita State University. Prior to receiving his doctorate from Michigan State University, he taught for seventeen years in the state of Washington, first teaching elementary general music and beginning band in Lake Stevens and then middle school and high school band in the North Thurston schools. He earned his Kodály certificate and Master’s degree from the University of Calgary. He has presented numerous clinics at state and national conferences and has presented three times at the Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic as well as having published articles in numerous journals. He directs the WSU Summer Kodaly Workshop (www.Wichita.edu/kodaly) which is one of the few programs in the country that has a separate track for secondary teachers as well as training for general music teachers.

Related Reading:

Performance Preparation Plan

The Ringmaster: Programming, Rehearsing, and Conducting the Beginning Band

Choosing Literature for Success at Contest: Every Concert Has a Purpose

If you would like to receive our weekly newsletter, sign up here.

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook too!

Learn. Share. Inspire.

BandDirectorsTalkShop.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.