One of the bassoon’s primary jobs is to play low notes. So, when those notes do not come out, players—students and professionals alike—are apt to respond with frustration and even panic. This article will lead you through the most likely causes behind a bassoon’s low notes not speaking and what you can do to help.

Whisper Key Issues

The first category of issues has to do with the whisper key, which closes the vent on the bassoon’s bocal. If this vent is left even partially open in the low range, notes become difficult to produce.

Bocal vent not lined up with whisper key pad:

The bocal should be inserted into the top of the wing joint as far as it will go and positioned so that the whisper key closes flush against the bocal vent.

Missing or damaged whisper key pad:

If the pad is not there (or is only barely there), it cannot close the bocal vent. The good news is that this is perhaps the easiest pad to replace on any woodwind instrument. As long as you have a lighter or alcohol lamp, stick shellac, and the right size/shape of replacement pad (they vary by instrument brand–consult a repairperson or double reed supply store to make sure you have the right ones on hand), you can fix it in a matter of minutes by following any number of online video guides. In a pinch, a damaged pad can be held together with a piece of electrical tape.

Wing joint misaligned:

If the wing joint is not lined up properly, the mechanism that holds the whisper key closed on Low E and below will not function properly. Most bassoons have marks on the wing and boot joints that show the proper alignment. Sometimes the marks are not exact, though, and the wing joint mark needs to be positioned just a little before or beyond.

Wing joint-boot joint connection showing alignment marks

Missing or damaged bumper:

The bridge that allows the pancake key to also close the whisper key should have a rubber bumper. If the bumper wears down or falls off, the whisper key will not close all of the way. This can be easily remedied with a new bumper (from a repairperson) or a few courses of electrical tape.

Whisper key bridge with blue electrical tape used to build up worn bumper

Loose screw:

If one of the pivot screws holding the whisper key rod in place becomes loose, the whole mechanism may not close as intended. The screw at the bottom of the whisper key rod is usually the culprit. If it keeps backing out, a coat of clear fingernail polish over the screw and onto the post will keep it in place.

Bottom of whisper key rod with screw in place. The screw at the top of rod can be seen in the first picture of this article.

Other Parts of the Bassoon

The second category of issues has to do with other parts of the instrument.

Bent Low C-D connection or worn felts:

Three of the four low note thumb keys on the bassoon’s long joint are connected in a way that allows one key to close one or two of the others. If the Low C-D connection gets bent or if the felt under the keys wears down, the mechanism goes out of alignment and the low notes stop speaking clearly. The best fix will be provided by a skilled repairperson. But, with a little patience, thought, and bravery, you can make some decent adjustments on your own using a bit of medical tape (to narrow the gaps where the felt has worn down) and/or a pair of toothless needle-nose pliers (to gently re-bend the Low C-D connection).

Long joint Low C-D connection

Backed-out screw rods:

If the screw rods (or pins in older instruments) holding the long joint’s low note keys in place have begun to back out, the keys they hold will wobble and not seal properly. Simply screw them back in.

Other missing pads:

In addition to the whisper key pad, if a pad is missing anywhere else on the instrument, any notes below that missing pad will either be extremely difficult or impossible to produce. Most missing or damaged pads are best replaced by a skilled repair person.

Split bocal:

If the bocal has even a small split in it, the whole instrument becomes difficult to play. To test for a split, have the student plug both the vent and the cork end of the bocal with their fingers and then suck the out the air out of the bocal through the reed end. If the bocal loses suction quickly or does not hold suction at all, the bocal has a leak (probably a split along its seam). A small split can be temporarily patched with a piece of electrical tape. Permanent patches can be made by a skilled repairperson.

reeds

The third category of issue deals with reeds.

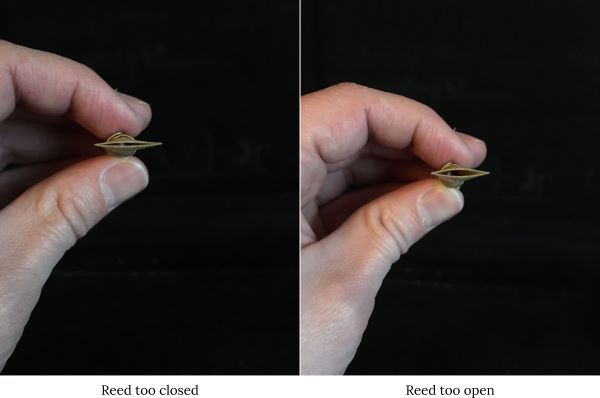

Reed too closed or too open

The tip of most reeds should be open about a millimeter at the center. If the reed is closed down further than this, the low notes can be difficult to produce at anything other than a quiet dynamic. If the reed is too open, barely anything will come out. To remedy, first make sure the entire reed has been soaked long enough (about two minutes unless the reed started very, very dry), then use a pair of pliers to gently squeeze the wire nearest the tip until the tip has the desired millimeter opening at the center.

Reed not sealing around the bocal:

Sometimes a reed leaks air out the back, making it difficult to articulate low notes. A reed that leaks in this way will often have water bubbles coming out of the back of the reed when it is played on the bocal. There may also be a hissing noise audible to the player. The first solution is to make sure the entire reed has been soaked long enough (about two minutes unless the reed started very, very dry). If the problem persists, the fastest (though temporary) solution is to wrap a piece of paper once around the tip of the bocal before putting on the reed. A more permanent fix using wax or wire can be made by an experienced reed maker.

Reed placed on bocal over a piece of paper to seal air leak

the player

The final category of issues deals with the player.

Wrong fingerings:

Fingerings for low notes are pretty straightforward, but this does not always keep a student from learning them incorrectly.

Improper thumb placement:

If a player does not have their left thumb in position to properly close the low note keys (especially on an instrument that has bent key connections, worn felts, or backed-out screw rods), the pads may not seal as well as they need to. Since thumb length, strength, and flexibility vary greatly from person to person it is hard to make specific recommendations other than to help the student find a position that is both comfortable and mobile.

Embouchure too tight:

If the player’s embouchure is too tight (especially top-to-bottom), the low note fingerings will produce harmonics instead of the desired fundamental pitch. For ideas on how to help a student with their embouchure, consult the excellent article HERE.

This list of possible issues is surely not exhaustive, but it should cover the majority of low note issues. Of course, low notes are always easier with a well-built reed, but reed adjusting is a whole topic of its own. If problems persist after checking the issues listed above, it will be best to take the student and the instrument to a private teacher so the teacher can have a closer look at both.

Bassoonist and educator Dr. Ryan D. Romine serves as Associate Professor of Bassoon and Music Theory and Assistant Dean for Recruitment at Shenandoah Conservatory (Winchester, VA). Originally from Newark, OH, Ryan holds degrees in music education (The Ohio State University) and bassoon performance (Michigan State University). Recent projects include an album of French contest pieces (Première), a first-ever publication of Jacques Ibert’s Morceau de lecture for bassoon and piano, and a book on bassoon extended techniques (Bassoon Reimagined).

Related Reading:

Do Bassoonists Really Need to Use the Resonance Key?

Demystifying Double Reeds

The Non-Bassoonist’s Guide to Equipment

If you would like to receive our weekly newsletter, sign up here.

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook too!

Learn. Share. Inspire.

BandDirectorsTalkShop.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.