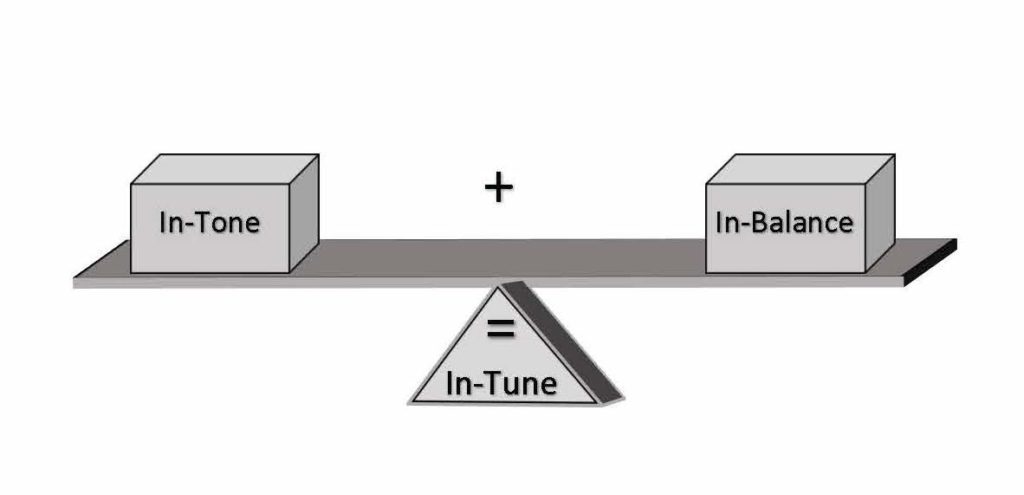

These three concepts: Balance – Tone – Intonation, are considered a trio so to speak. All three share a symbiotic relationship in which each benefits the other. The ability to play in tune is a skill that cannot be adequately developed until a student is able to consistently play with a characteristic tone and proper balance. And when good tone is balanced among all members of the ensemble, then good pitch can be a direct result.

These three concepts: Balance – Tone – Intonation, are considered a trio, so to speak. All three share a symbiotic relationship in which each benefits the other. The ability to play in tune is a skill that cannot be adequately developed until a student is able to consistently play with a characteristic tone and proper balance. And when good tone is balanced among all members of the ensemble, then good pitch can be a direct result.

Quality tone must serve as the foundation for the development of ensemble skills. The characteristic sound of each instrument is determined by the presence of overtones in the sound. Each note is made up of its fundamental frequency along with higher overtone frequencies. It is this harmonic series that determines the characteristic tone color of each instrument. The insistence on good tone is the responsibility of the ensemble director. The lack of such doggedness may contribute to the player’s notion that good tone is of minimal importance.

Tone quality is essentially influenced by five basic factors:

- Director’s concept of tone for each instrument

- Student’s concept of tone for their instrument

- Student’s ability to produce a characteristic tone

- Ensemble balance and blend

- Color and texture influenced by nature of repertoire

Directors may best describe characteristic tone to their students by playing quality audio recordings. Students cannot be expected to emulate a sound that they have never heard. Once an aural imprint has been made, only then can we set expectations for our students to tame their tone to a consistent quality of sound production. Provide your band parents with a list of quality wind and percussion artists that their children can download to their mobile devices or listen to online. Concert streaming has revolutionized the accessibility of live concerts by bringing programs straight to your classroom and living room.

Try this exercise with your students to start developing a vocabulary for describing various tone colors and qualities.

Exercise

Find a repertoire selection that has been performed and recorded by at least two different artists. Bring these recordings to class. As you listen to the tone of each player, write down all the “color” words that best describe their tone.

| Artist # 1 | Artist # 2 | Artist #3 |

| Dark | Bright | Sweet |

| Brown | Yellow | Green |

| Smooth | Edgy | Flowing |

| Chocolate | Lemon | Pudding |

| Sonorous | Thin | Compact |

| Pure | Clear | Cloudy |

| etc. | etc. | etc. |

Note: These color words are not intended to be complete, nor do they belong only to the groupings displayed above. These are only suggestions for brainstorming a list of adjectives with your students.

(This exercise is from p. 48 in Teaching Instrumental Music: Developing the Complete Band Program, 2nd ed. by Shelley Jagow Copyright © 2020 Meredith Music Publications, a Division of GIA Publications, Inc.)

Building Balance in the ensemble is a unique blend of tonal elements. Blend comes about when two or more tones merge with one another to achieve unity of sound. Balance comes about when two or more tones combine with one another to achieve a complementary sound. Ed Lisk (1987), in Alternative Rehearsal Techniques (Meredith Music Publications), illustrates the concept of balance and blend in relation to the fundamental or bass voice of the ensemble, which he calls “the basic law of sound,” and “the basic law of ensemble pitch.” The director must first concentrate on the quality of sound of the fundamental. If there is little or no bottom to the band, or there is a poor quality of sound to the bottom of the band, then it will be difficult to achieve balance and blend. Additionally, all sections that include 3rd and 4th parts must be balanced to the upper parts. Traditionally, many students who do not play the 1st part feel they do not equally contribute or are as equally important as the 1st part players. 1st parts may be the most important from a melodic perspective, but the lower parts are more important from a harmonic perspective. Directors must emphasize to students the importance of the sum of ALL parts to the whole.

Teaching students to listen beyond their own printed music on the stand will increase their awareness of musical roles and how they need to play their role for that particular moment in the piece. In simplistic terms, the more notes in your measure or the darker your part, then it is likely it is of melodic versus harmonic importance. And conversely, the fewer notes in your measure or the lighter your part, then it is likely your role is of harmonic versus melodic importance. Refer to Francis McBeth’s system of pyramid of ensemble balance system when describing the concept of balance. Lower-voiced instruments reinforce tones of middle and higher-voiced instruments due to the natural harmonic overtones of lower instruments. In general, higher voices may be played softer because less volume is required for them to be heard over lower voices. A director should plan for annual instrumentation needs with a minimum four-year projection chart. This allows you to look ahead to see what students will be graduating and, therefore, what instrumentation needs to be replaced. As a general rule of thumb, the brass instruments should never outnumber the woodwind instruments.

Keep in mind that printed dynamics in the score are only relative — qualified by issues such as instrumentation and balance, as well as stylistic and interpretive decisions. When rehearsing ensembles with limited instrumentation, it is practically necessary to rewrite the dynamics in the player’s parts in order to offer musical honesty to the piece. On unison ensemble crescendos, the lower voices/instruments should crescendo slightly faster than the higher voices/instruments in order to maintain a solid balance during dynamic modulations. Failure to follow this approach will result in a crescendo that will sound top-heavy. An effective approach is to ask the lower voices to crescendo to almost 100% capacity, the middle voices to crescendo to 75% capacity, and the higher voices to crescendo to only 50% capacity. The ideal effect should result in a properly balanced sound.

Once a strong fundamental of ensemble tone quality and balance is achieved, we can look more closely at intonation. Equal tempered tuning is a system that evenly divides the 12 half-step intervals in an octave. Most fixed keyboard instruments are tuned to the equal temperament scale. However, instrumental ensembles should be tuned using pure intervals instead of equal intervals if they truly desire to refine their tuning and intonation because pure intervals sound with increased resonance when compared to equal intervals. This is largely due to the natural properties of intervals found in the harmonic series.

By following a Just Intonation Interval Chart like the one found in Tuning for Wind Instruments: A Roadmap for Successful Intonation (2012, Meredith Music Publications), you will have an immediate reference for ensemble tuning of chords. And an alternate fingering chart for tuning chords is available for both Android and iOS from Google Play and the Apple App Store. An ensemble chord will sound in tune when the proper frequencies are sounded based on the root of the chord. All of the chords illustrated in the Just Intonation Chart are based on root C, but the pitch adjustments illustrated will occur on each of the twelve equal-tempered roots. The symbol (+) indicates a pitch correction by raising the pitch of the note from equal-tempered tuning, while the symbol (−) indicates a pitch correction by lowering the pitch of the note from equal-tempered tuning.

For example, in a Major chord, all players sounding the Root must play at equal temperament (or zero pitch on a tuner). All players sounding the Major 3rd must lower the pitch by 14 cents, and those sounding the Perfect 5th must raise the pitch by 2 cents. Players should listen for beats as a guide to making the necessary adjustments, as illustrated. A beatless chord will sound more consonant and, therefore, in tune. A chord played with equal temperament will produce slight beats and will sound slightly dissonant and therefore out of tune.

Tuning is not just something we do at the beginning of each rehearsal. Tuning is an ongoing process. Tuning at the beginning of rehearsal is merely used to place the instruments at their correct length and to wake up the ears for active listening. The remainder of the rehearsal includes ongoing attention to fitting each pitch within the sounding overtones of the ensemble by listening down to the lowest voices. In order to achieve such beat-less tuning, students must learn how to manually adjust their pitch by such means as air, embouchure, and alternate fingerings.

Shelley Jagow is director of the Wind Symphony and Concert Band and teaches instrumental conducting courses at Wright State University (Dayton, OH). She is a Vandoren Artist Clinician, as well as a music education clinician for Conn-Selmer, GIA, and Meredith Music. Shelley is the author of Teaching Instrumental Music: Developing the Complete Band Program (2nd ed.), (Meredith Music), Tuning for Wind Instruments: A Roadmap to Successful Intonation (Meredith), Intermediate Studies for Developing Artists on the Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Saxophone and Bassoon (Meredith), and The Londeix Lectures—a multi-DVD set archiving the historical lectures of Jean-Marie Londeix (and translated by William Street). Website: www.shelleyjagow.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.