Most young jazz bands can do an excellent job learning the notes and rhythms of a tune, but something keeps them from making a tune really swing. Getting a good swing feel in a band of any age and experience is one of the most difficult elements of jazz. So many factors go into it. The drummer has to have a clear feel on the ride cymbal, the bass player has to be locked right onto the drummer for time, and the horns have to be listening to what the rhythm section is communicating. On the horn side of the band, the lead alto, trumpet, and trombone also have to be of like mind. Being the highest pitched instrument and perched in the back of the band, it is the lead trumpet’s job to communicate forward to the others how the horn sections should be playing in terms of style of attack, how laid back to play, and cutoffs. This means the lead trumpet has to be especially tuned into the rhythm section. To use an analogy, the drummer is the engine that powers the band, the bass player serves as the wheels to get you places by outlining the chords, and the lead trumpet is the driver, keeping everyone on the road.

What follows are three of the key elements of playing swing lines that young jazz bands tend to struggle with, a solution on how to improve it, and some big band charts to showcase mastery.

Rushing the last two eighths

From experience, one of the hallmarks of a novice band is when the last two eighth notes of a swing line are rushed/compressed. The line up to that point can be swinging, but then it is as though the needle is yanked across the record, pulling it out of the groove. There are a variety of possible reasons why, but what it comes down to is the listener being jarred out of hearing a cool line at the worst time. Players need to always feel the swing accent and communicate that to the audience.

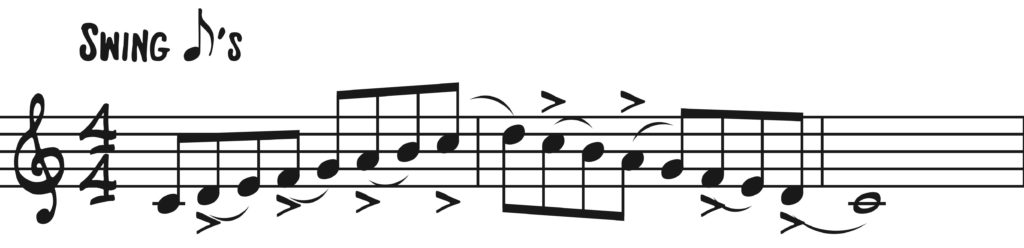

In order to get players in the habit of swinging to the end, a scale routine can be useful. Moving around the circle of fourths, play up to the 9th and back down, following a pattern of slurring to the beat. This articulation pattern also helps to reinforce the upbeat swing accent, triplet rhythmic offset, and legato articulation throughout, all keys in making a line swing. Some standards of the big band library that can showcase this are Duke Ellington’s Satin Doll, Neal Hefti’s Li’l Darlin’, and Sammy Nestico’s arrangement of Witchcraft.

Suggested group exercise

Late off an eighth rest

While not unique to jazz bands, being late off a rest will throw off a line and wreck a groove faster than anything. Rushing to catch up is not an option. Rests are not a stopping point, but rather a silent part in the music. In jazz, they especially help to clarify the rhythm. With all of the syncopated rhythms, adding eighth rests for notational clarity is standard practice with publishers and engravers. They are also used to indicate note length, with an eighth note followed by an eighth rest being more clear than a quarter note with an articulation mark.

To help young players understand that the rest is more about rhythm than a stop or breath spot, have them play the line and continue the note before the rest into the rest, eliminating the rest but maintaining the rhythmic integrity of the line. Once they get the feel of where the line continues after the printed rest, play it normally to see if it sticks. Some charts to highlight this are Doug Beach’s New and Improved Blues, Neal Hefti’s Splanky, and Sammy Nestico’s Switch in Time.

Suggested group exercise

Keeping the line natural

Young jazz musicians have a tendency to try and keep all notes at equal volumes unless a dynamic alteration is printed. If asked to sing any of their lines, however, it is very likely there would be some natural inflection added. That inflection needs to be transferred over to the performance on the instrument. Typical notes to highlight are the peaks and valleys of fast melodic lines, usually comprised of eighth notes and indicating a direction change for the line. Other common accents, if thinking in 4/4, are the upbeats of beats two and four. Bar lines can be another limiting factor, so make sure players look at the whole phrase, not just the individual measures.

To work on this, have the sections sing their parts while the rhythm section plays. If there is disagreement, stress listening to the lead player. Lines like this will appear in the saxes more than the brass, so make sure the lead alto has a good concept of the tune. Most any chart with a sax soli will be useful to work on this. For the whole band, some options are Billy Byers’ All of Me, Neal Hefti’s Cute, Mike Tomaro’s Blue-Note Special.

Suggested group exercise

Jazz style comes with time and experience. Listening skills are crucial. A great assignment for developing bands is to have assigned listenings with the students writing reactions to what they heard. The act of writing holds them accountable for listening critically. Jazz has the same basics as concert band music, but students must immerse themselves in the sound to internalize the uniqueness of its style.

Kyle Millsap is Assistant Professor of Trumpet and Jazz and Texas A&M University-Kingsville. He oversees all aspects of the trumpet program, including applied instruction and directing the concert and jazz trumpet ensembles, as well as directing Jazz Band II and performing with the Kingsville Brass Quintet. He has performed and/or presented clinics at several state, national, and international conferences. For more information about Dr. Millsap or the trumpet program at TAMUK, visit millsaptrumpets.com or tamuktrumpets.com.

Related Reading:

Developing a Jazz Program: Strategies and Solutions

If You Build It, They Will Swing

Scale Clubs

If you would like to receive our weekly newsletter, sign up here.

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook too!

Learn. Share. Inspire.

BandDirectorsTalkShop.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.