Stopped horn is an extremely effective but sometimes misunderstood technique required for the horn. Stopped passages occur in every genre of music for the instrument, from solos and chamber music to large ensembles such as orchestra and wind band. There are various theories which explain the acoustical phenomenon, but they often fail to offer practical solutions. The following tips should aid in helping your students to produce a dependable, characteristic stopped horn sound

I. Proper open horn hand position is a must.

While the right-hand position is always important for horn players, it becomes crucial when hand stopping. Hand positions vary among professionals, but some general characteristics of a good right-hand position on the open horn are:

- Fingers bent at the knuckle and straight (but not flexed) from the knuckle to the tips of the fingers.

- Thumb is close against the side or top of the index finger, with no space between.

- There are no spaces between fingers.

- The palm of the right hand is slightly cupped.

- Right hand conforms to the shape and size of the bell—this will result in a slightly rounded shape when the back of the hand is pressed against the right side of the bell

- Line up the knuckle of the thumb with the bell brace, then insert hand until the thumb touches the upper part of the bell and pinky touches the bottom.

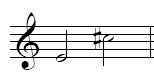

See Figures 1 and 2 below for a demonstration of these concepts, with the hand in and out of the bell of the horn.

Figure 1. Proper Right-Hand Formation

Figure 2. Proper Open Hand Position

II. The move from open to stopped horn must be practiced, striving for efficiency and minimal difference between open and stopped hand position.

The following ideas are helpful in practicing open to stopped horn. Consult Figure 3 at the end of this section for proper stopped horn hand position.

- A proper stopped horn sound is compressed and brassy. Obtaining this sound requires as leak-free a seal as possible between the right hand and the bell throat. Many stopped horn problems (poor intonation, fuzzy articulations, uncharacteristic sound, etc.) can be remedied by readjusting right-hand position.

- Avoid the temptation to shove the hand further into the bell, which will cause the pitch to be sharp. Keep the thumb pulled back and out of the way of the hand.

- Instead of attempting to close the hand perpendicularly across the front of the bell, close it at an angle. This decreases the area being covered, allowing for a better seal.

- Strive for as much contact as possible between the heel of the hand and the bell throat, and eliminate any leaks. Imagine you are squeezing the horn between your left and right hands. Slightly twisting the heel of the palm so that even more flesh is in contact with the bell is also helpful.

- Because of the dramatic increase in resistance with stopped horn, students sometimes do not blow strongly enough against that resistance to get the characteristic buzz associated with stopped horn. Filling out the sound of stopped notes will also help with intonation and articulation problems.

Figure 3. Stopped Horn Hand Position

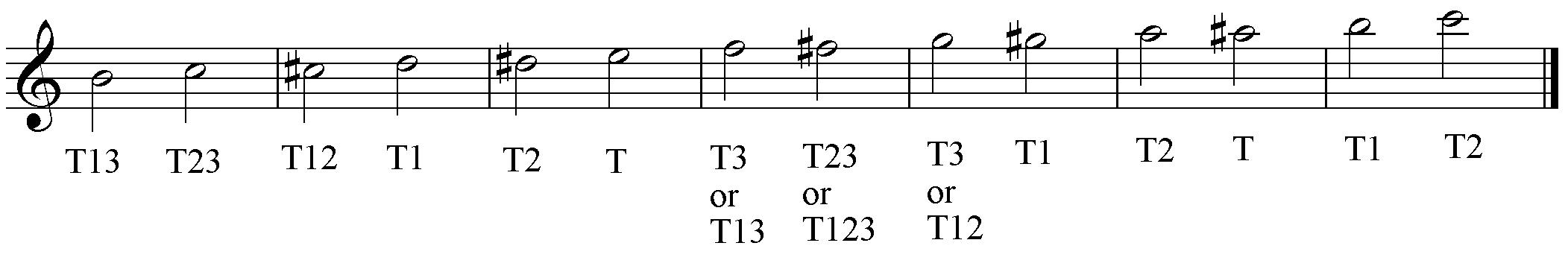

III. Experiment with alternate fingerings.

It is usually acceptable to use F horn fingerings and transpose down 1/2 step within the following range (all pitches are for horn in F). If the above factors are properly addressed, this range presents the least problems of intonation and articulation.

For the high register, F horn fingerings will work, but problems of accuracy and intonation become more exaggerated. For this range, the following fingerings are suggested. The abbreviation “T” indicates B-flat horn fingerings.

While these fingerings will work on most horns, there are also many alternate fingerings. The only rule one need follow when deciding on alternate fingerings is “if it sounds right, it is right.” If the intonation and sound quality are good, then it does not matter what fingering is used.

In closing, here is a final thought on working with stopped horn sections. When rehearsing stopped passages, players should perform the part on the open horn a few times so that they can get a better sense of pitch and articulation before attempting to play the part stopped. When they do play the part stopped, encourage them to really blow so that they can experience the sensation of producing a compressed, brassy sound.

Dr. James Boldin is Associate Professor of Horn at the University of Louisiana-Monroe and maintains a diverse career as an educator and performer. He has performed at four International Horn Symposiums and numerous regional horn conferences and is active as a soloist, and orchestral and chamber musician. He has published two books through Mountain Peak Music, and has released a solo recording with MSR Classics. For further information, visit http://jamesboldin.com

Related Reading

Playing the French Horn With No Arms – Amazing Story of Overcoming Challenges

Helpful Horn Hints: How to String a French Horn Valve

Avoiding the Most Common Pitfalls – Tension!

If you would like to receive our weekly newsletter, sign up here.

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook too!

Learn. Share. Inspire.

BandDirectorsTalkShop.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.