Musicians often write about and discuss the importance of breathing in band performance. While some hold the position that a healthy body takes care of its own respiration, I can say first hand that there’s a lot of psychological interference when you take that body and put a piece of metal, wood, or plastic in front of it (as well as a piece of sheet music). I would urge band directors to do their diligence in seeking out those materials to better understand and teach healthy respiration, proper body alignment and posture, and breathing exercises. However, for this article, I want to focus on the next step, transferring good, healthy breathing into a musical performance.

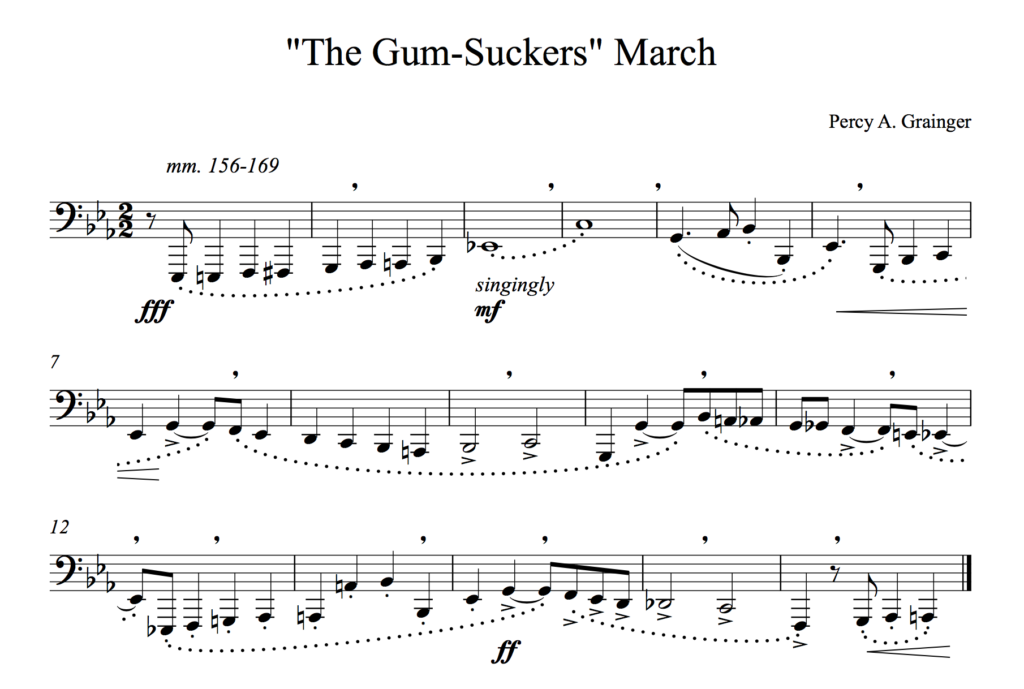

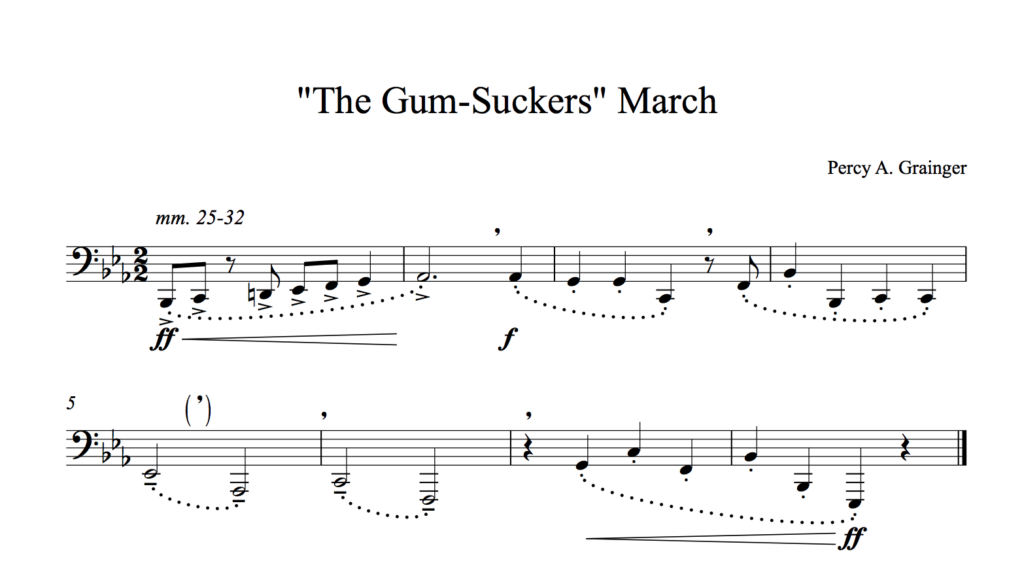

A few years ago, I visited and worked with the low brass section of a prominent 6A Texas high school band. They were performing advanced literature and, overall, handling it masterfully. Nevertheless, I noticed some problems with their tuba section. In their trying to make very long phrases (or perhaps not being sure where to phrase), they were playing only until they ran out of breath. The result was not only diminishing tone quality as they progressed, but the students never actually learned their parts in the areas where they would perpetually run out of air because they didn’t get that daily repetition. Lastly, one of the works programmed was Grainger’s The Gum-Suckers’ March. Grainger purposefully and playfully elides phrases, and so the adage of not breathing on bar lines doesn’t always apply.

My takeaways:

- Students need to have a breathing plan (a marked-up part) that allows for a breath whenever it is needed, so long as it does not interrupt the musical phrase. Breathing exercises will teach students how to make those quick orchestral intakes.

- The music that we perform is so diverse, as are the needs of different ensembles, that simply telling students not to breathe on bar lines, while a good rule of thumb, is not a substitute for encouraging them to make a breathing plan of their own. They will not necessarily feel empowered to breathe on their own in other places without your instruction.

When I was in high school, I vividly remember listening to and studying Gene Pokorny’s Orchestral Excerpts for Tuba album. I had marked Pokorny’s audible breaths into my assigned excepts for the week, and was pleased to bring them to my private lesson. My teacher at the time Scott Mendoker rightly pointed out that Pokorny dwarfs my 5’10” frame, and that I would, in fact, need to breathe more frequently to even attempt to achieve the same success that he did on that recording. Not to mention that, on the recording, Pokorny himself discusses some of the differences between auditioning with and performing this music.

My takeaways:

- The breathing plan may not be the same for each player, depending on their size, ability, and even their instrument type and size (bore size, etc.).

- A breathing plan for how to prepare an excerpt for audition may not be the same as one for an ensemble performance.

Now, all of this sounds very complicated, but really it isn’t. You’ve either determined that it’s not necessary to teach breathing (if your students are healthy and respire as they normally should), or you use a specific methodology to teach many aspects of musical breathing. I’m simply asking you to help your students transfer that knowledge into their band performances and auditions. Teaching them a good unison starting breath, as I’m sure that you do, is a nice place start, but what about all the other breaths in a work? I have never had a high school student show up to a private lesson with breath marks on their region band or college audition music, for example. Students should be taught how to make a breathing plan for their repertoire.

My own plans often include parenthetical, emergency breaths, in case I miss a crucial breath, or I do not happen to take in enough air. It might sound like micromanagement, but it’s the same as writing in fingerings when learning an instrument in a new key or a different kind of trigger system. Eventually, you won’t need to write them any longer as you build new habits. If you do not build better habits, you’ll be plagued by your old ones. You’ll be teaching page one of your exercises year after year with the same marginal results. Writing in breaths is how students learn to breathe enough, breathe more, and breathe better.

One last student to evaluate is ourselves. Is coming up with a generalized breathing plan a part of your score study and preparation process? Do you consider which instruments or players might need to breathe more often? I would encourage you to consider that telling students a few crucial places not to breathe (by marking an “NB”), while helpful, is not a substitute for your making a breathing plan (in the same way as telling them not to breathe on bar lines does not suddenly make them know where and how much to breathe).

Sometimes, stagger breathing is a useful option, but it can be unnatural, and it must be coordinated and taught. (For example, do you want a diminuendo before a breath, a soft release, and soft entrance, and then a crescendo back to full volume? If so, you must teach that.) Lastly, we’re all inundated with the notion that longer phrases are better as if we’re constantly in the middle of double and triple period structures. Are there ways to incorporate musical breaths that do not chop up a phrase? I think that there are. Singers and choirs do this all the time with great success, and the instrument that we all most aspire to emulate should be the human voice.

I challenge you and your students to discuss and make a breathing plan for each work studied that empowers them to breathe as often as needed, likely more often than they already are. It will improve their range, accuracy, tone, comfort, dynamic and articulation control, and stamina. As long as they do not do anything unnatural that causes hyperventilation, the results should only be positive. After all, air is free, so let’s use it!

Jeffrey J. Meyer, D.M.A. Jeffrey Meyer is currently the Director of Bands and Brass Studies at Sul Ross State University. He received his Bachelor of Music from the Eastman School of Music, Master of Music from Kent State University, and Doctor of Musical Arts from the Cleveland Institute of Music. Meyer is an active conductor, clinician, and adjudicator. He has served on the faculties of the Cleveland Institute of Music, University of Guam, Highland Community College, El Paso Community College, and the Luzerne Music Center. Meyer received a Higher Education Fund to found and maintain the electronic music studio at Sul Ross. He also directs the pit orchestra for the Theatre of the Big Bend and the Big Bend (TX) Community Band.

Related Reading:

The Fine Art of Legato

4 Tips to Help Beginner Tuba Players

Diagnosing Brass Tension and Helping Students Achieve a Better Sound

If you would like to receive our weekly newsletter, sign up here.

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook too!

Learn. Share. Inspire.

BandDirectorsTalkShop.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.