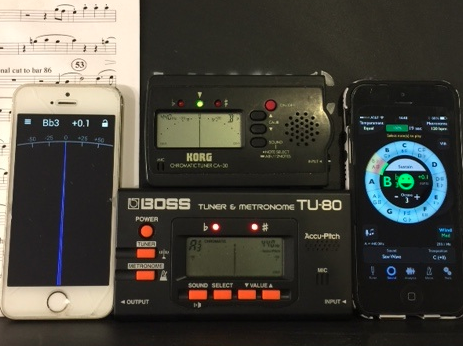

I firmly believe that the Tuner Teaches Tendencies and as the student develops, they must continually be aware of their own tendencies. If I rely too much on a tuner, I feel like I am improving my eyes more than my ears, so I employ a variety of solutions/sequences to avoid eye-training:

- First play with your eyes closed. Then open your eyes and check the tuner, and adjust as needed. Close your eyes again, and focus on the sound and try to memorize what that pitch sounds like when perfectly in tune. Use “slow-motion slurs” to bend the pitch up and down. Developing this level of flexibility is a great vehicle for finding the pitch center.

- If you can practice in front of a mirror, turn the stand to face it and watch the tuner’s reflection instead of the tuner itself. Since the direction of the needle movement is reversed, this disrupts the tendency to “train your eyes”, and puts the onus of intonation on the ear more than the eyes.

- Have a friend watch the tuner for you, and tell you if you are out of tune. They could tell you if you are sharp or flat, they may use hand gestures (pointing up or down), etc.

Electronic Drones

Listen, match, and memorize. Using an electronic drone will help the student not only match the pitch of the drone itself, but also practice just intonation and playing exact intervals based on that drone. I personally recommend using tonic, dominant, or any common tones.

Ensemble Experience

Nothing beats playing in a band or chamber ensemble for perfecting the ability to match, blend, and balance.

Listening

Having your students listen to recordings of themselves can help them hear and understand what kind of adjustments they need to make, and adding a tuner to the mix helps them see and hear what they really sound like. Oh no!

Alternative Methods

“Eye to Ear” Illusions for Pitch and Intonation

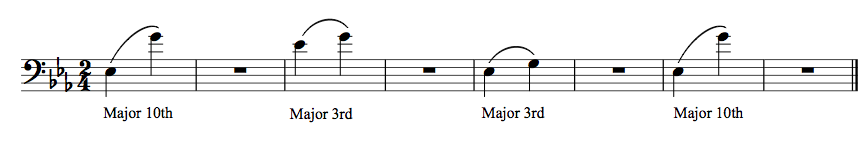

Example: F major arpeggio

On most brass instruments, the third partial tends to be sharp; in this arpeggio, played without adjustments, the F3 may be sharp and the A3 tends to be flat, so the distance between them needs to be adjusted in order to be in tune. Measures two and three include different enharmonic spellings of notes to visually change the distance between the notes. As a player, this helps me reinforce all physical habits associated with adjustment and I essentially trick myself into playing in tune.

This concept can be used to address additional intervals by simply changing the desired distance based on the individual’s needs. With the growing access to notation software mixed in with our smart devices, this concept can easily be applied to any instrument in the band.

Moving Drones

A melody with numerous recurring pitches, such as the Chaccone theme from First Suite in E-flat for Military Band by Gustav Holst, is useful for practicing pitch consistency. In the example below, I have isolated the F3 and the B-flats to be played by another student, or by a recorded drone; this can easily be accomplished by recording these long notes with a metronome and tuner, and then using this recording as your duet partner.

Holst, First Suite in E-flat for Military Band Op. 28 Op. 28 No. 1 with moving a drone duet

Transposition Techniques

This technique uses octave transpositions to condense intervals larger than a perfect fifth. For example, the opening interval of the E-flat etude in the Voxman Selected Studies for Baritone, which was included in the 2018 All-State Band audition material, is a major 10th (E-flat3 to G4). If the student is not able to hear where to put the second note, then they are likely to hit other partials with the same fingering (D4, F4, and A4 to name a few). If your student has no trouble with the upper-register but seems to be hitting notes at random, try the following steps:

Step 1. “Everyone goes up”

Play all notes close together in the high range (E-flat4 to G4). This may also apply to more than one note but for our purposes, we will only focus on E-flat and G which are now only a major 3rd apart.

Step 2. “Everyone goes down”

Play all notes close together in the low range (E-flat3 to G3 and still a major 3rd apart).

Step 3. Play as written

The process of playing intervals in various octaves creates smaller intervals which are much easier to hear and this can even allow students to start hearing in octaves! When I apply this concept to large leaps I find much more consistency without staring at a tuner.

Dr. Danny Chapa currently serves as the adjunct professor of low brass at Stephen F. Austin State University and is also a member of the Lone Star Wind Orchestra, principal trombonist of the Odysseus Chamber Orchestra, and frequently performs guest artist recitals at various universities, conferences, and conventions around the country. In addition to performing, Dr. Chapa has developed an ongoing lecture series entitled, “I Talk, Euph Play” in which he discusses and expand upon material taken from his dissertation and independent research. These lectures have been presented at several tuba-euphonium conferences in collaboration with euphonium players from various premier military bands.

Related Reading:

Tips on Teaching Intonation (from 50+ Band Directors)

How to Teach Focused Listening

Listen With Your Eyes: Identifying the Physical Roadblocks Behind Common Performance Issues

If you would like to receive our weekly newsletter, sign up here.

Don’t forget to like us on Facebook too!

Learn. Share. Inspire.

BandDirectorsTalkShop.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.